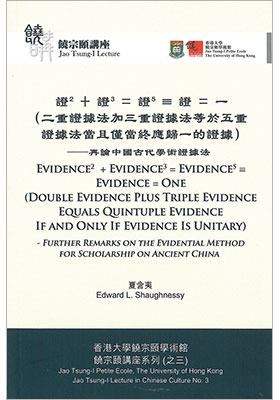

Evidence2 + Evidence3 = Evidence5 ≡ Evidence = One (Double Evidence Plus Triple Evidence Equals Quintuple Evidence If and Only If Evidence Is Unitary)

Further Remarks on the Evidential Method for Scholarship on Ancient China 再論中國古代學術證據法

(證2 + 證3 = 證5 ≡ 證 = 一(二重證據法加三重證據法等於五重證據法當且僅當終應歸一的證據))

ISBN : 978-988-12977-1-6

Distributed for HKU Jao Tsung-I Petite École 香港大學饒宗頤學術館

August 2014

116 pages, 5.5″ x 8.25″, 6 color illus.

- HK$70.00

Also Available on

王國維先生所提倡的「二重證據法」是整個二十世紀中國古代文化史上最有名的研究方法。然而,1982年饒宗頤先生又提出了「三重證據法」,就是在王國維「紙上之材料」和「地下之材料」以外,再加上物質文化證據。在2003年,饒先生又談了學術方法,又增加了兩種「間接史料」,即「民族學資料」和「異邦古史資料」。甚麼叫做證據,要怎樣利用證據,要怎樣判斷證據的輕重都是歷史學家的先決問題。王國維和饒宗頤的觀點可以算是現代史學的主流,在夏含夷合編的《劍橋中國古代史》裏,兩位編輯就採取了這個觀點作為該書的基本構造。雖然如此,該書出版了以後,編輯們發現不是所有的學者都接受這一觀點。有兩種書評發表,從兩個不同的立場提出尖銳的批評,一個說這個做法輕視了中國傳統文獻,一個說太重視傳統文獻的歷史性,因此是「不科學的、不客觀的」。在這本書中,夏教授先對二十世紀的史學觀點做一個簡單的總覽,然後比較詳細地討論《劍橋中國古代史》的編輯工作和讀者反應。

Throughout the twentieth century, the “Double Evidence Method” advocated by Wang Guowei was the most important research method for the cultural history of ancient China. However, in 1982, Jao Tsung-i proposed a “Triple Evidence Method,” adding material culture to the “paper sources” and “underground sources” of Wang Guowei. In 2003, Jao again discussed scholarly methods, and added two more “indirect” types of evidence: “anthropological sources” and “ancient historical sources of other countries.” What constitutes evidence, how to use evidence, and how to decide the weight to give to evidence are the first problems encountered by historians. The views of Wang Guowei and Jao Tsung-i can be considered as the mainstream of contemporary history, and in The Cambridge History of Ancient China, of which Edward L. Shaughnessy was co-editor, the editors adopted this methodology as the basic structure of the book. Nevertheless, after the book was published, the editors discovered that not all scholars accept this viewpoint. Two book reviews were published raising pointed criticisms from two different standpoints: one said that the editors had under-emphasized traditional Chinese literature, while the other said that they had over-emphasized the historicity of traditional Chinese literature, and because of this their results were “unscientific” and “non-objective.” In this book, Shaughnessy first provided a brief overview of twentieth century viewpoints regarding historical research methods, and then gave a more detailed discussion of the editorial work on and readers’ responses to The Cambridge History of Ancient China.